You can also view this newsletter as a PDF.

Mental Health: Raising Awareness, Reducing Stigma

An Introductory Note from the State Controller:

Over my close to eight years of service as State Controller, my office has benefited from the talent and perspectives of student interns who have the opportunity to support the policy deputies on my team, as well as to work on operational initiatives. This summer, I met Sarah Yee (no relation), a high school junior who is an aspiring journalist. As we spoke about some of the issues and challenges over which we shared mutual concern, Sarah identified mental health – a topic that has gained increasing importance in my role as a member of the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) Board of Administration, where its health plans are facing a shortage of behavioral health providers.

Aware of this, Sarah spoke about the unaddressed mental health challenges among youth, especially relating to her and her peers in the Asian American and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander communities, the high rates of suicide among these youth, and the loss of their full societal and economic potential. Sarah asked to write a feature article highlighting this growing mental health crisis, to help increase awareness. After reading it, I was taken aback by the deeply personal perspectives Sarah expresses. With parental permission, I feature them here.

October 10 is World Mental Health Day, for mental health education, awareness, and advocacy. Too often, this work lacks a focus on youth. I hope the youth voice here will sound a call to action for reducing the risk factors affecting people’s mental health, expanding the numbers of trained and culturally competent behavioral health professionals, enhancing their work conditions, and creating the conditions necessary for people to thrive.

– Betty T. Yee

Feature by Guest Author Sarah Yee...

No one ever explicitly told me not to talk about my mental health, but the omission was enough.

2020 taught me how to treat this wound for the first time—by pouring a little alcohol on it, caustic and cool to the skin.

I took this treatment to heart, particularly when the anti-Asian hate waves began flooding the headlines. I tried not to be as caustic as the alcohol I had poured over my wounds but I couldn’t stop questioning: Why now, when our community is being verbally and physically harassed, are Asian Americans finally being recognized? Why must we reach a point past hurt in order to even recognize a need to heal?

As a journalist, inquisitive by nature to a fault, I searched for an answer. An answer to the questions of a clear identity turned cloudy in 2020. Who was I? Chinese or American, Chinese-American? Externally I traced the slant of my eyes, myself in the eyes of others — the shape of my grades, stark, sharp divides of the acceptable As to underline my American name?

A girl who in every contortion to conform still misses the modeling mark?

For how could I call myself a proud Chinese if I couldn’t speak more than a few words of my ancestors’ native tongue, Cantonese? How could I call myself a proud American if I was singing to the land of liberty, the same land where my mother ventured into supermarkets with pepper spray, sunglasses and a bent head?

I recall coming to school on days I had math exams, on days that I didn’t but I was counting down to when I did. I recall gripping the desk until my knuckles bled white and numb, in an attempt to alleviate the blankness filling my head, a human reminder to breathe. I recall the tears trickling down, embarrassingly slow as I console myself and others around me, “I’m fine,” the punctuation more like a question than a period. This period shall pass, my thoughts chorus.

I recall coming to school on days I had math exams, on days that I didn’t but I was counting down to when I did. I recall gripping the desk until my knuckles bled white and numb, in an attempt to alleviate the blankness filling my head, a human reminder to breathe. I recall the tears trickling down, embarrassingly slow as I console myself and others around me, “I’m fine,” the punctuation more like a question than a period. This period shall pass, my thoughts chorus.

I’m in a period of eternal jet lag from my immigration six generations ago from Canton, China.

I’m a passenger, outlined in red like the curve of my last four quiz curves. D for Don’t Come Home, also Don’t Come Here, our home is not yours. Six generations later, I am still a foreigner.

D for disintegration, destruction of identity, home filled with hate.

I shudder. I’m not ok.

It’s not ok to ignore the signs, the statistics, the stories like my own that silently scream Asian-American (AA) and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (NHPI) youth are not ok. True awareness and appreciation for Asian Americans is not found amongst headlines of hate, but in addressing and equipping its very frontlines — the youth that stand for tomorrow.

The pandemic has only exacerbated the xenophobia and bigotry against the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community and within this, the underlying mental health crisis and accessibility challenges the community faces. Given the 339% increase in AAPI-related hate crimes in 2021, understanding the downstream effects is paramount. According to the 2021 national report for Stop AAPI Hate, nearly 1 in 5 AAPI adults have experienced a hate incident in the past year. These incidents disproportionately target AA and NHPI women and the elderly, but the effects on all AA and NHPIs cannot be understated.

In Stop AAPI Hate’s 2021 mental health report, almost half of AA and NHPIs reported anxiety during the pandemic and an even greater percentage were “more stressed by anti-Asian hate than the pandemic itself.” One in five who experienced racism further reported symptoms of racial trauma — “the psychological or emotional harm caused by racism” — with symptoms similar to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Multiple studies have cited an increased association between racial discrimination and mental disorders. In young adults, 1 in 3 AA and NHPIs reported clinically elevated symptoms of depression and general anxiety, and 1 in 4 reported a PTSD diagnosis.

Statistics around AA and NHPI youth suicides tell a similar story. The Mental Health Association (MHA) reports, “Suicidal thoughts, plans, and attempts are also rising among AA & NHPI young adults. Forty percent of LGBTQ youths who are AA and NHPI have seriously considered suicide in the past year. More than half of AA and NHPI LGBTQ youth experienced discrimination based on their race/ethnicity in the past year, numbers higher than pre-pandemic ones. Aggregated, suicide is the first leading cause of death among AA and NHPI youth (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2021), and the second leading cause of death for all American youth (CDC, 2021).

Yet even before the world reeled from COVID-19, AA and NHPI mental health disparities were evident. When broken down by race, suicide is the leading cause of death among Asian American young adults aged 15-24. This is true of no other racial group in this age range in America (CDC, 2017). Similarly, among Asian Americans aged 20-24 years, suicide is the leading cause of death, accounting for 33% of deaths compared to 21% for Whites, 15% for people of Hispanic origin, and less than 10% for non-Hispanic Black people. According to a 2019 CDC report, death rates for Asian or Pacific Islander males aged 15-24 increased from 9.1 in 2000 to 15.5 deaths per 100,000 resident population in 2018. Similarly, death rates for Asian or Pacific Islander females increased from 2.7 in 2000 to 6.8 deaths per 100,000 resident population in 2018.

Though these statistics should speak for themselves, even more paramount are the stories behind them – the true challenges the AA and NHPI community and youth face within the microsystems (intimate relationships), mesosystems (interrelations between both systems) and macrosystems (social and political institutions) that dictate and constrict their environment.

Per my student journalist experience, to uncover the story, we must dig deeper.

The risk factors of suicide and depression among AA and NHPI youth are numerous, including mental illness, low self-esteem, sexual orientation, immigration and acculturation status, family relationships, language proficiency, and the model minority myth.

One of the biggest factors are common “myths” that still permeate society’s perception and ultimate response to the actions and interactions of the AA and NHPI community. The biggest of these myths is the “Model Minority Myth,” an amalgamation of “positive” attributes that stereotypes all Asian Americans as stoic academic and financial successes.

Yet the Model Minority Myth holds gross implications for the challenges Asian Americans face. The truth of this myth is its erasure – erasure of individuality and self-internalization and minimization of racism and elevated tensions between other minorities.

Far from a monolithic block, there is great diversity among AA and NHPIs. The fastest growing ethnic group in the U.S., AA and NHPIs consist of around 24 million Asians composed of over 50 nationalities. We do not all model the same expression. The very way we express ourselves through our cultural models differ.

While aggregated data shows the composite AA and NHPI community possess the highest average household income, disaggregated poverty rates and median household income reveal “the majority of Asian groups with a history of refugee resettlement (i.e., Bhutanese, Cambodian, Hmong) had median household incomes well below the median household income for all Asian American-led households.” Eight to twelve out of nineteen Asian origin groups have poverty rates as high as or higher than the U.S. average.

The roots of mistrust and unwillingness many AA and NHPIs have demonstrated towards not only seeking mental health resources, but general healthcare, travel back to a similar pandemic – a San Francisco bubonic plague outbreak where the government paralleled its xenophobia by burning down Chinese living quarters. This is the part of history that I was never taught. This is the part of history that must be.

The roots of mistrust and unwillingness many AA and NHPIs have demonstrated towards not only seeking mental health resources, but general healthcare, travel back to a similar pandemic – a San Francisco bubonic plague outbreak where the government paralleled its xenophobia by burning down Chinese living quarters. This is the part of history that I was never taught. This is the part of history that must be.

The mistrust is mutual, and the feeling seemingly perpetual, that no matter how long Asian Americans have been in America, they still do not belong and never will. Their identity will always be a ceaseless marker, modifier of who they are as a myth.

It is these myths that amplify mistrust in healthcare and contribute to underrepresentation in the crucial research we need not just to understand the AA and NHPI community and the voices of the next generation from a healthcare perspective, but also an honorific historical one. True acknowledgement of the hate crimes that have manifested themselves so readily over the past two and a half years starts with understanding the past.

These myths tread under the surface, festering as microaggressions and rearing in overt acts of assault against the AA and NHPI community. The roots that sprouted these feelings have been here since Asian Americans arrived; since my family – the six-going-on-seven generations of Yees – arrived in the early 19th century in search of “Gam Saan,” to weave themselves an American dream out of glistening strands.

These myths craft a narrative of stoicism, ambivalence towards Asian Americans and NHPI: that we are successful, models with painted faces and feelings; no real attempt made at healing the gaps within and outside of our community to address mental health.

Other cultural factors that AA and NPH face are between the highly individualistic culture of the U.S. vs. the more collectivistic culture prevalent across Asia. Acculturation status plays a large role in the status of an AA and NHPI’s family mental health. The impact of these culture clashes on mental health is evident in the “burden” many AA and NHPI youth voice shouldering when they speak out about their own mental health. Likewise, intergenerational trauma, passed through generations, can be transmitted through adverse experiences either emigrating from or immigrating to the United States. Most critically, one can experience its effects even if they themselves did not directly undergo trauma.

Even six generations down the line, I still shoulder the burden of expectations, the hopes and fears that my great-great-great-great grandfather surely had as he left everything behind to immigrate and launch his later successful herbal store in the Central Valley. I shoulder this invisible weight every day I walk into a room, every day in the guilt I feel for how much “easier” I have it than those in the past. I feel guilty even for feeling guilty, and I can’t imagine how those most directly connected to immigrants (the second generation that is largely AA and NHPI youth like me) feel.

The current mental health resources available to AA and NHPI, much less AA and NHPI youth, are challenged in their ability to access the largest stakeholders and to bridge the persistent and negative perceptions towards mental health – the stigma and the shame that accompany speaking out for yourself, much less being cognizant of others’ mental health.

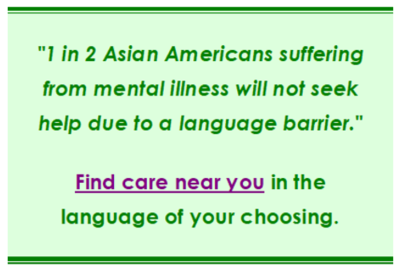

Common accessibility barriers include language, immigrant status, wealth and other health access gaps. Of these, arguably the largest challenge lies in language. According to the APA Commission of Ethnic Minority Recruitment, Retention, and Training, 1 in 2 Asian Americans suffering from mental illness will not seek help due to a language barrier. The Central Valley alone reportedly has “the most specific language groups that had more than 1 in 5 households having linguistic isolation with 11 groups.” Within these linguistically isolated households, the diversity of language is clear – Chinese and its dialects may encompass the “largest Asian language group in California with well over 1.2 million speakers,” but other language families like Tagalog and Punjabi are also common. Overall, 32.6% of AA and NHPI Americans are not fluent in English, and rates of proficiency vary within specific subgroups; 44.85 of Chinese, 20.9% of Filipinos and 18.7% of Asian Indians are not fluent in English. Additionally, 60% of AA and NHPIs aged 65 years and older have limited English proficiency (Source: NAMI CA). Accessibility efforts should also acknowledge more vulnerable subgroups of the AA and NHPI community, such as the elder community.

Evidently, to address the dearth of AA and NHPI youth and their families seeking therapy, we must first address the dearth of Asian-American and generally BIPOC psychologists. According to APA's (American Psychology Association) Center for Workforce Studies, in 2015, 86% of psychologists in the U.S. workforce were white, 5% were Asian, 5% were Hispanic, 4% were Black/African-American and 1% were multiracial or from other racial/ethnic groups, with other mental health professions being “similarly homogeneous.” Without providers that are well-versed in the unique risk factors and culture-bound syndromes AA and NHPI face – like “Hwa-byung,” a Korean syndrome similar to major depression according to NAMI – improvement in symptoms and mental health literacy will be marginal and even discourage AA and NHPI from seeking professional support again.

My first counseling experience was in the ninth grade in the midst of the pandemic. Like many, I was overwhelmed by the internal and external conflicts I battled with daily; like many, I turned to social media for solace; this turned to depressive episodes and anxiety attacks. Shakily that September, I filled out my school’s wellness referral form. Shakily, I shut the door to my room for my first counselor conversation. Shakily, I answered her questions. Then came the consent question.

Stopping the spread of suicides amongst AA and NHPI youth starts by educating and involving the parents. Parents are an integral part of AA and NHPI youth’s microsystems, and their perception of mental health largely influences their child’s likeliness to communicate their mental health to them. Targeted outreach towards AA and NHPI youth must also involve the parents at some level, whether it’s through family therapy or education efforts to reframe the language often exchanged within the community (“You’re acting crazy”) and potential inflammatory language exchanged to the community –terms like ”psychotherapist” that reinforce negative stereotypes.

While it’s imperative for all mental health providers to understand the cultural nuances that can affect the AA and NHPI community’s reception to mental health services, it’s also critical for school counselors.

While I’ve been fortunate to have school counselors who are devoted to learning more about the challenges AA and NHPI youth particularly face in accessing mental health, I understand that these sentiments and even the ability to see a counselor at school are not felt by many. School counselors, as the frontlines to AA and NHPI students, must be well-versed in the risk factors for suicide for AA and NHPI youth, able to empathize with both students and parents through understanding cultural context, and most importantly, be willing to learn more about the diverse body of student stakeholders they ultimately serve.

Culturally cognizant care looks like tailoring treatment around the already existing beliefs and Eastern treatment options in AA and NHPI communities. Initiatives to decrease the stigma while improving mental health literacy can look like acknowledgment of traditional treatment like acupuncture, ayurveda, meditation, etc. Community bonding activities that can incorporate mental health awareness can include aromatherapy, poetry and more.

Culturally cognizant care looks like tailoring treatment around the already existing beliefs and Eastern treatment options in AA and NHPI communities. Initiatives to decrease the stigma while improving mental health literacy can look like acknowledgment of traditional treatment like acupuncture, ayurveda, meditation, etc. Community bonding activities that can incorporate mental health awareness can include aromatherapy, poetry and more.

Similarly, understanding the suicidal ideation statistics among AA and NHPI youth means analyzing the risk factors in the systems that surround them – from the microsystems that comprise interpersonal relationships, to mesosystems of tradition and networking and macrosystems of social and political institutions.

The challenges the AA and NHPI community faces on a macrosystemic level bring a clear 2020 vision.

In the past two years alone, thousands of anti-Asian hate incidents have been reported with over 40% occurring in California, home to the nation’s largest AA and NHPI population. According to the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism, anti-Asian hate crime was more than three times higher last year than the year before, with San Francisco and Los Angeles (cities deep in their own history of anti-Asian prejudice; think of the discriminatory laundry laws and the 1871 Los Angeles Chinese Massacre) surpassing their record numbers in 2020.

When considering justice for these crimes, leading AA and NHPI advocacy movement #STOPASIANHATE emphasizes holding offenders accountable for the “physical and emotional harm” inflicted.

The increased attentions towards the AA and NHPI community must not be temporary but resolute to fully address and change the infrastructures that exist around treating rising AA and NHPI youth suicide rates and assisting AA and NHPIs with their mental health.

Already, awareness has birthed action.

A little less than a year ago, on Oct. 19, 2021, the American Academy of Pediatrics alongside the Children’s Hospital Association (CHA) declared a “National State of Emergency in Children’s Mental Health.” Responses to recognition efforts like the aforementioned declaration include bills with an emphasis on mental health education – notably the bipartisan Rosen-Murkowski bill which expands direct funding nationwide for suicide prevention and mental health promotion education, particularly in K-12 school districts; and a 2022 California mental health education bill to require one or more courses in health education for pupils in middle or high school to include instruction in mental health. The bill would require the State Department of Education to develop a plan to expand mental health instruction in California public schools on or before January 1, 2024. Similarly, the passing of the California Assembly Bill 1767 in 2019 requires local education agencies in California are required to adopt and update a policy for students grades 1-12 on suicide prevention that specifically addresses the needs of high-risk groups.

The few AA and NHPI mental health-specific bills include Judy Chu’s introduction of the “Stop Mental Health Stigma in Our Communities Act,” (May 28, 2021) which empowers organizations like SAMHSA and others to enact established educational strategies to “curb mental health stigma in the Asian American and Pacific Islander community.” Other notable legislation efforts include President Biden’s plan to fund Bright Futures, a federal partnership with the American Academy of Pediatrics to add universal screening for suicide risk to national guidelines for people ages 12 to 21. Efforts like these spotlight the unheard stakeholders. What strategies can society take to educate, empower and empathize with their experiences?

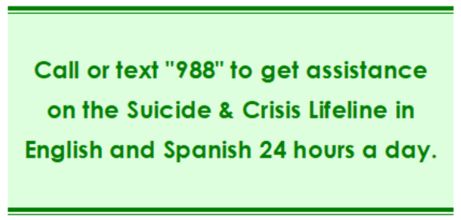

Within the Greater Sacramento area, I have access to multiple free and paid mental health resources, including Asian and Pacific Community Counseling and the Wellness Center at my school. Online, resources are even more expansive, including The Trevor Project’s 24-hour confidential hotlines and the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline.

Within the Greater Sacramento area, I have access to multiple free and paid mental health resources, including Asian and Pacific Community Counseling and the Wellness Center at my school. Online, resources are even more expansive, including The Trevor Project’s 24-hour confidential hotlines and the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline.

Just a few weeks ago, I attended an Asian American Youth Mental Health Circle hosted by the Asian American Liberation Network (AALN) co-led by none other than Sacramento’s very own National Youth Poet Laureate, Alexandra Huynh. The circle was liberating in its constructed casualness – the effort taken to put participants at ease with ample food from across AA and NHPI cultures and an ambiance that encircled the event’s goals. Even sitting in a circle crafted a closer connection: participants, professionals and organizers were connected, inside the circle in some way.

This connection, desire to be listened to and moreover understood is what’s missing in most efforts to target AA and NHPI youth. If it is hard enough for me as an AA and NHPI youth myself who feels compelled to voice my thoughts on serving the population I call home, it is surely harder for other AA and NHPI youth without incentive to share their stories when everything they’ve learned in the differently tiered systems that comprise their lives sings of shame, sings of stigma.

The lark cannot sing if its voice has been bound by centuries of barriers, without even a common language to communicate. Fluent culturally conscious communication extends beyond language fluency; it means reading the stories woven between the unspoken and spoken languages of the diverse AA and NHPI community.

The phoenix cannot rise above if “above” lies only a lack of love.

The phoenix cannot rise above if “above” lies only a lack of love.

In other words, I find most AA and NHPI youth are not able to break down the barriers that encircle them because those in their closest circle – their families – are not truly within that circle. The connection I was able to form within that circle in mere hours – where I was able to share – is still missing. It’s up to us, our society both inside and outside the “circle” – within and outside the AA and NHPI community – to amplify the voices we need to bridge this circle of connection. And it’s up to people, particularly AA and NHPI youth like me, to amplify the voices we hear, to stitch the strings (the risk factors and statistics behind AA and NHPI youth mental health) into a story as impactful as we deserve.

Writing stories like these is the precursor to true awareness. Sharing them spreads awareness. Shaping them with culturally relevant strategies signals the simultaneous action and awareness we need to decrease AA and NHPI youth suicide rates and increase communication between all the different strands of youths’ lives.

The first time I called a crisis line was just weeks ago; the first time I utilized one at any level (texting, mobile chatting) was two years ago. The dates are murky but the specifics of the interaction, both emotional and technical in the messages exchanged from both sides of the line, are outlined in 2020 vision – befitting of the timely backdrop. I remember the surge of shame I felt on both occasions – that I had finally given in to my “demons,” “personal problems;” that I was weak for not just needing but wanting help. I remember feeling ashamed for vocalizing my story when there were others that needed to be heard, others that I felt were more deserving than mine and of the faceless screen’s, speaking abyss’s time. I scream but it is a silent one.

Shakily enveloped by the dark

of my closet, I squeak, shuffle.

Hello?

A voice resounds.

A simple “hello” was the helping hand I needed in one of the most raw moments in my life where I felt I had everything but grasped nothing. It was a moment where I felt trapped in my roles – my identity as a Chinese American, a daughter, a team player, an editor, a writer, an advocate for an issue I struggle so much with myself and struggle so much more so to write about.

I hope that this article is a “hello” to those in need, and a louder “hello” to those not in need. I acknowledge, it takes time for these stories to be rewritten.

It takes one dinner “table talk”

about mental health to start.

One suicide to stop the crisis of not caring.

One metamorphosis for the caterpillar to

break the changeless cycle.

One community so vastly different yet defined

by cultural homogeneity to change the paradigm

of mental health wellness.

Sixteen Strings and Stanzas: A Poem by Sarah Yee

It took me a beleaguered and uncomfortable month to share my story; the sixteen strings and stanzas represent my journey through mental health:

1.

I weave into this tangled textile

strand for sixth generation, chorus a string, stories

of Chinese Americans sloped across California’s golden “Gam Saan” hills

carpeted cascades bearing gold interlaid between red, white and blue

within these folds, sound the promissory notes of the American dream

resounding through the glistening valleys, bridging the bleeding

tumbling tourniquet, tournament, trials

long winded dials, love letters to home

2.

my culture is not a curse

my name will not jest on your lips in a cursed verse

inverse my identity, Chinese or American

chart the changes delta x over delta y through the ages

independent variable-my identity

dependent variable- my irrational individuality

are these Ds on my transcript, accented accidents of defiance or desperation?

slope steepens towards salvation

I pitch forwards on an incline, dangling string in tandem by country’s threadbare design

3.

the chime, times have changed their tune

too late to realize, too invested to go home

what glistens gold bleeds cold

harken epidemic of expulsions

hear marginalization of myths

our stories written over our mouths-are we a myth, myths?

closed captions over our academic records

main attractions, main detractions

licenses of our identity, licensure to the amenities of America

past the expedited speeding limit

something or someone does not belong on this gold gilded highway

to drive or to drive out

such animosity pierces the first string of my story

cut the cord

dissonant

disowned

it.

Asian American voices

4.

present prescience of pulmonary embedments

string in my lungs, stifling

Scapegoats and slander reek of political pandering

scrape to history, setting default-projectile virus

festering fight or flight within ambivalent amygdala

so cues presidential popularity issues

take them up with your tissues

soak white carpets of cotton

snow blanket these red, white and blue hills

5.

ply pandemic pressures to pulp

epidemic encroaches upon 2020 vision

murky in blotted out investigative, journalistic questions

masterclass musing

reigning principle 1: do good journalism

2: AP- Answer the Prompt

Chinese or American? exclusive, both, none?

check mark in all of the above?

as I hum to the hymn of headlines, hate hurting and healing

mangled motley of microaggressions falling

flailing familial frontlines, punctuated in pepper spray

accented in supermarket English

two tongues, aisles forked in two

universal signs cue; shop, stay in your own lane.

enduring quarantined contagions entice my shame

fester in my name, the arduous answers

not American enough

not Chinese enough

a girl who in every contortion to conform still misses the modeling mark

final mark: not enough.

6.

Asian academic fails

blooms red kite tails, trails across my

fabric laced in letters, Ds, I can’t send home

math exams grant master classes, class keys to my

closet of consolation, publicity speaks

emblazoned in desperatory, declaratory acts

I stamp, red into a colonial war

peace accords I grasp and grimace under the table

the parents are talking

Mine.

all locked arms, faces and doors with no keys

key to readability, indicators of ease

internal pleas, please

7.

I wish I could do the math

calculate the extremas of my daily dissection

where is the limit?

I ponder my priorities

American amenities shot through gold

unfulfilled Freudian monstrosities

calculate….

DNE-does not exist.

8.

16th warrior wielding Olivia Rodrigo lyrics

strung through wired ears, pulsing fleeting, fiery questions

where’s my insert obligatory expletive teenage dream?

I don’t feel 16.

I feel like a string, wavering under the wind

bridged over teenaged and childhood between

adult identification timeline unforeseen

attempting to rewind back the time, lingering, longing finds

9.

24 hour alarm awash alcohol over my I.D.

caustic, causes water recession

retention over middle school recollections

I shudder in successions, lament the questions

moving, choosing, losing

meanderings to call home here

10.

Home-work

lost keys and responsibilities trend

ties to my wallet

letting, leaving sirens pinging down the stairwell

well buried in solemn stones, coins dropped by weary, worried well fishers, full time wishers

etched in my name, my face, my blame

moon of disappointment never wanes

11.

I step onto the wrestling mat

diss appointed on opponent myself

uniform an untrue red white and blue

bound by a slipping grip

have patience, putts quick

in slide and dice, die on dial

wedging every course appearance

within rounds of record court trials

rough not the fair way, follow through

where the ball lies on tufts of iron

tightened tee off kelter

club-clawing conscience pressurized in melter

mush, much ado about mistakes

hole in one game of life

sweeps my feeble strings, swings in strife

12.

table talks more like expository walks

life stories in rarely conversed languages

past heritage and present privilege framed, inflamed

in my prerogative-heat the pressure cooker

that inflames, drafts my name

in designatory lock and block rafts, echo “emails I can’t send,”

I too, confess Sabrina Carpenter and other album compilation confrontations

following the cacophonous symphony of explaining

emotions to artists crafted, conditioned to stigma

interlace “mental illness,” with “personal problems,”

imply privacy is a requisition not a permission

commissions of confidentiality denied

tried and trues paths-deep outer and inner room cleans, sleep solutions prescribed

hissed keep this in the “confines,”

cold case dismissed, 16 year practiced linguist needs no lists

follow your proclamatory guidelines

you’ll be fine.

13.

face planted face palms

fall, felling rigid hands of red

caught red handed in a tumbled web

of threads, reworked seams of self

through the looking glass, who am I?

a girl, slipping down the rabbit hole

I spy the world, a golf ball in one hand, pen in the other

where do I lie, to what claim do I testify?

14.

advocate or hyphenated hypocrite

paying toll in trigger terms- exit then enter depression, anxiety

trepidation to speak the “s word”-suicide?

toast to this intersection of identity, past and the present

loft looms picturing myself, the victor

having nimbly traversing the spider’s lair

or spun into fodder, caught in the crosshairs

lying carpetless-red, white, blue and gold stripes stripped to the standard mold

seeking- Asian American youth mental health evaluation

game of among us, entrusts another statistic on a long list

needling, never published

my respect rusts

Red

15.

pain as I explain

eyes veiled in disdain

at the place I occupy, weather non dependent

hot-lines chill cold calls

name misplaced in shivering scrawl

I am not your expectation at all.

16.

phone pressed against ear, I squeak to speak

“Hello?”

fine line strains in a side bend

arcs lopsided across generations and the gaps between

bring warmth to the huddled figure

blanket her in the memories quilted in

the hurt, the hope, the healing, the simultaneous rewind and reeling

I hear, don’t question the resurgence, only recall resplendence of sensational feeling

like light let through a shadow box

I press my inked hands, shade words of worth

16 strands intertwined in geometric

aesthetic, blistering perception of personal and my people’s history

arithmetic, academic muddled, meaningful transcriptions, role play rejections

slowly thread the reddening needle through self reflections, circular community affection

I rise at this inflection, state to release the weight

16 strings too many.

I find most Asian American youth are not able to break down the barriers that encircle them because those in their closest circle-their families-are not truly within that circle. It’s up to our society both inside and outside the “circle” of close community to amplify the voices we need to bridge barriers. And it’s up to people, particularly Asian-American youth like me, to stitch the strings of our stories into a singular strand as impactful as we deserve.