You can also view this newsletter as a PDF.

Controller Yee: Time to Shift Culture to

Close Diversity Gap at Private Equity Firms

According to long-standing research by McKinsey & Company, public companies in the top quartile for gender diversity were 25 percent more likely to outperform industry-median growth than companies in the bottom quartile. Similarly, executive teams in the top quartile of ethnic diversity were 36 percent more likely to financially outperform the industry median.

This is why large investors – like the California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS) and California State Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS), on whose boards Controller Yee serves – have spent years engaging with public companies to ask for greater board and C-suite diversity, to help protect the earnings they need to ensure long-term sustainability for their retirees.

These efforts, along with societal pressure and customer expectations, are now yielding results. A recent report from SpencerStuart showed the 2021 class of 456 new board directors is the most diverse ever, with 47 percent ethnically diverse new directors compared to 22 percent the year prior. Still, there is room for improvement, as only 21 percent of all S&P 500 board directors are ethnically diverse. Women comprised 43 percent of all new directors in 2021, down a little from 47 percent in 2020. Ongoing efforts to add more women directors have gradually increased the total share of S&P 500 female directors to 30 percent.

The trend toward greater diversity has the support of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), which recently approved Nasdaq’s new rule to require that its listed companies publicly disclose board diversity statistics each year, and that they have at least two ethnically diverse directors. SEC Chair Gary Gensler also announced the agency is developing proposals on enhanced human capital management disclosure – including diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) – which, if adopted, will help investors continue to engage public companies and push for change. Despite the progress and encouraging trends at public companies, privately held companies lag far behind. This is problematic, since the number of public companies has declined by almost 50 percent over the past 20 years, down from approximately 7,000 in the mid-1990s to 3,451 currently in the Wilshire 5000 index.

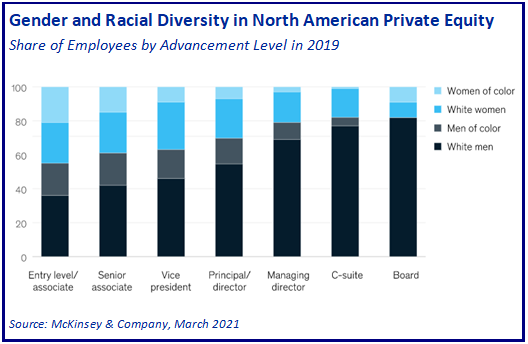

Gender and racial diversity at private equity – or PE – firms are stronger in entry-level positions than at the top. In fact, at the start of 2020, about 20 percent of senior leaders at private equity firms were women, while the share of women on executive teams in the rest of corporate America was about 30 percent.

Gender and racial diversity at private equity – or PE – firms are stronger in entry-level positions than at the top. In fact, at the start of 2020, about 20 percent of senior leaders at private equity firms were women, while the share of women on executive teams in the rest of corporate America was about 30 percent.

Globally, approximately 10,000 PE firms have more than $3.9 trillion in assets under management. In North America alone, there are 4,700 firms that own more than 18,800 companies. A recent Boston Consulting Group (BCG) survey found that, collectively, private equity-owned firms generate about 5 percent of U.S. GDP and employed almost 9 million people in 2019.

Controller Yee believes it is important to start shifting the culture at private equity firms. Many thought leaders agree that private equity firms have a unique opportunity to drive change faster, given that their ownership structure allows them to place their employees on the boards of the portfolio companies they own.

BCG’s survey of 4,000 employees in U.S.-based public and private firms found that private equity-backed companies have fewer programs and initiatives to promote DEI than public companies. They also are slower to respond to calls for change from employees and stakeholders. Often, private equity firms are more focused on scaling up the portfolio company’s profits than building the infrastructure to support DEI.

Since May 2020, the number of private equity firms focused on DEI has started to increase, as public pressure and engagement by investors like CalSTRS and CalPERS grow. By holding the firms in which they invest accountable, institutional investors are protecting their capital and the long-term sustainability of the funds. As they each pursue a greater share of co-investments, they also will have greater sway in the management and operations of the firms.

In its March 2021 report, McKinsey & Company suggests private equity firms establish an internal council on DEI to develop metrics, set goals, and monitor progress for the firm and its portfolio companies. They can conduct diversity assessments throughout the deal lifecycle by building DEI criteria into due diligence of potential investments of firms and investment committee reviews. McKinsey also recommends firm and portfolio company diversity metrics be reviewed at all partner meetings, and executive compensation be linked to these targets.

Within portfolio companies, McKinsey suggests it is important to set diversity targets for boards to position candidates with relevant skill sets. They also can establish diverse management teams to improve culture and performance. Finally, they should review and revise corporate policies throughout their portfolio to improve retention and promote equity in advancement of a diverse workforce.

The Institutional Limited Partners Association (ILPA), comprising investors who work with private equity general partners, recently captured many of these recommendations in the ILPA ESG Assessment Framework. This tool addresses DEI by asking firms to release a public statement or strategy addressing recruitment and retention of diverse staff, track internal hiring and promotion statistics by gender and ethnicity, adopt organizational goals that result in more inclusive hiring and retention, and provide demographic data during any new fundraising. The ILPA framework also requires firms to choose two additional initiatives from a menu of nine to further enhance DEI, such as incorporating DEI in employee performance reviews, providing demographic data for all investment funds, and a commitment to promoting diversity within boards of directors at portfolio companies.

Just like the call for increased transparency from public companies, the level of transparency around internal targets and outcomes is crucial to increasing diversity in the PE sector. Controller Yee believes investors should continue to engage with the private equity firms with which they work to ensure this key sector of the economy does not miss out on the proven benefits that come from having diverse staff and boards.

Housing 101: Understanding California's Finance Committees

The California Debt Limit Allocation Committee (CDLAC) and California Tax Credit Allocation Committee (TCAC) form the backbone of California’s affordable housing finance system. These committees allocate federal resources and limited state funds to privately owned developers of public necessities. CDLAC and TCAC create public-private partnerships to advance public development priorities. As a voting member of these committees, Controller Yee helps ensure resources are distributed in a way that maximizes public benefit to the people of California.

The California Debt Limit Allocation Committee (CDLAC) and California Tax Credit Allocation Committee (TCAC) form the backbone of California’s affordable housing finance system. These committees allocate federal resources and limited state funds to privately owned developers of public necessities. CDLAC and TCAC create public-private partnerships to advance public development priorities. As a voting member of these committees, Controller Yee helps ensure resources are distributed in a way that maximizes public benefit to the people of California.

CDLAC allocates state and federally tax-exempt bonds for the financing of affordable housing projects, homeownership programs, environmental projects, and mass transportation projects. These bonds are known as Private Activity Bonds (PABs). Each year, the federal government allows each state to allocate PABs up to a set limit. In 2021, California was allowed to award up to $4.33 billion in PABs to governmental bond issuers across the state to finance approved developments.

TCAC allocates federal and state Low Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTCs) to affordable multi-family housing projects. There are three types of LIHTC allocated by TCAC: 9 percent federal tax credits; 4 percent federal tax credits; and California state tax credits. Nine percent federal tax credits are limited by an annual federal cap. In 2021, this amount is $110.7 million in annual 9 percent tax credits – or almost $1.11 billion in total tax credits over the 10-year credit period.

Four-percent tax credits are automatically available to affordable multi-family housing projects that receive an allocation of PABs from CDLAC. State LIHTCs are allocated to projects that also are awarded federal LIHTCs. In 2021, $609.7 million in state tax credits were available for affordable multi-family housing projects. In 2021, the federal government has provided California with $80.7 million in additional annual 9 percent disaster recovery tax credits for wildfire recovery ($807 million in total value over a 10-year period).

In 2019, CDLAC allocated its full allotment of PABs for the first time in more than a decade. This increase in demand and awards is due mainly to the high level of resources state and local governments have dedicated to affordable multi-family housing in recent years. TCAC’s 9 percent and state LIHTC allocations have been over-subscribed for several years. The excess demand for PABs and LIHTCs provides California with an opportunity to ensure the award process incentivizes state priorities.

In 2019, CDLAC allocated its full allotment of PABs for the first time in more than a decade. This increase in demand and awards is due mainly to the high level of resources state and local governments have dedicated to affordable multi-family housing in recent years. TCAC’s 9 percent and state LIHTC allocations have been over-subscribed for several years. The excess demand for PABs and LIHTCs provides California with an opportunity to ensure the award process incentivizes state priorities.

Increased demand for PABs has reduced the availability of funds for environmental, transportation, and homebuyer programs. Affordable multi-family housing projects receiving PABs generally leverage more federal subsidies than other types of projects, since only affordable multi-family projects receive 4 percent federal tax credits. Recent federal tax law changes have increased the value of these tax credits to around 35 percent of a typical multi-family housing project’s development cost. The housing finance committees also have recently prioritized the construction of new affordable housing projects over the rehabilitation of existing projects.

The vast majority of affordable multi-family housing projects built in the last decade in California have utilized financing awarded by CDLAC and/or TCAC. No other single funding source is used as frequently as PABs and 4 percent federal tax credits to build these projects. In combination with the 9 percent and state credits awarded by TCAC, regulations developed by these committees drive the state’s affordable multi-family housing development. Financing for multi-family projects from local governments and other state and federal programs generally is only used if the projects are awarded PABs and/or LIHTCs.

CDLAC and TCAC long have served as an integral financing source for several state priorities. The increased demand for PABs through CDLAC places more pressure on CDLAC to allocate these limited funds in a more efficient and effective manner. Moving forward, input from all interested parties will help ensure priorities are properly identified and incentivized.