You can also view this newsletter as a PDF.

Wildfire Behavior Heightens Focus on

Forest Management as Risk-Reduction Strategy

Fire is a natural and essential process, and wildfires have occurred throughout California history. However, since 2000, California has experienced a substantial increase in the frequency of large wildfires, often with devastating effects on people and property. Of California’s 10 most destructive wildfires of all time, all but one has occurred in the last 15 years.

Wildfires of the past usually burned slowly and low to the ground. The result was that fires thinned out brush and smaller trees, leaving the larger trees to thrive with less competition for water and sunlight. The big, healthy trees could spread out more evenly, leaving patches of open land that were less susceptible to fire. Periodic low-intensity and mixed-severity fires also resulted in a mosaic of conditions that kept the forests healthy.

Fires now burn hotter and longer with continuous fuels. Decades of fire suppression and timber harvests have created unhealthy forests with canopies so dense that fires can spread easily and be far more destructive.

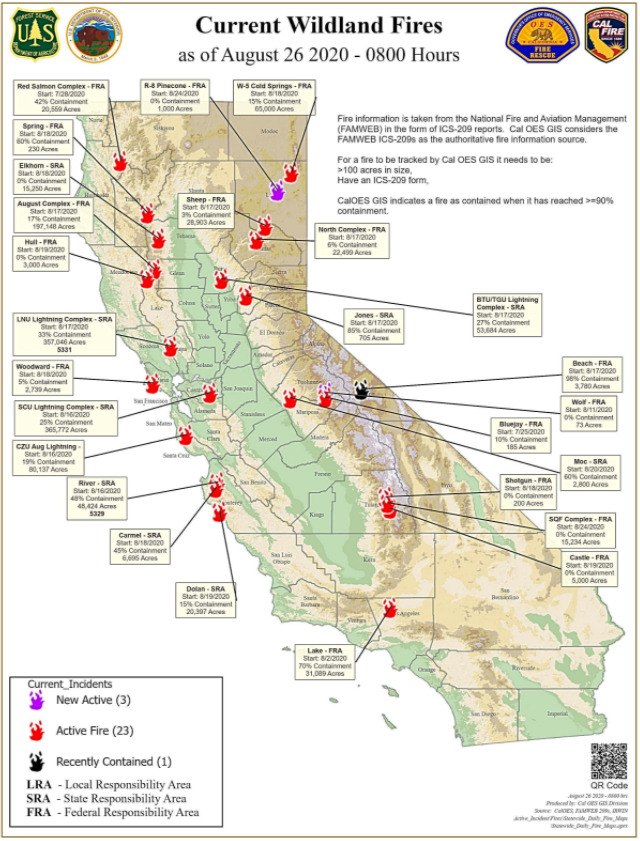

Climate change has exacerbated wildfire risk and damage. In a 72-hour period in mid-August alone, California experienced more than 10,000 lightning strikes. Within the week, 560 known fires were burning throughout the state.

Climate change has exacerbated wildfire risk and damage. In a 72-hour period in mid-August alone, California experienced more than 10,000 lightning strikes. Within the week, 560 known fires were burning throughout the state.

As air temperatures rise, more intense heat waves in summer and fall cause soil and plants to dry out sooner and create additional fuel for fires. These trends were worsened by the five-year drought that began in 2012, which left trees weakened and vulnerable to disease and insects. More than 130 million trees died in the drought, providing fuels for fires. High-severity fires pose public health risks by harming air quality and damaging the state’s water system.

The 2017 and 2018 wildfire seasons were the most destructive in state history, causing $40 billion in losses and fire-suppression costs. In 2018 alone, 8.7 million acres burned. The Camp Fire in 2018 was the single most destructive fire, taking the lives of 88 people and destroying most of the towns of Paradise, Magalia, and Concow in a single day. The Camp Fire destroyed more than 18,500 structures and cost an estimated $15 billion.

Wildfire prevention, mitigation, and response activities are costly. Currently, more than 20 million acres of U.S wildland are classified as being under “very high” or “extreme” fire threat. Making significant improvements, through the periodic use of prescribed-fire and forest-thinning techniques, could cost billions of dollars over many years and would need ongoing maintenance to secure ongoing benefits. Moreover, jurisdiction over the forests complicates any solutions. The federal government owns a vast majority of forested land in the state – 19 out of 33 million acres – while timber companies and other private landowners own 14 million acres. The State of California owns and has direct control over less than three percent of forested lands.

Nonetheless, California leaders continue efforts to repair forest health, protect people and property, and work with federal and local partners to respond to and prevent wildfires. Since the 2018 fire season, the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFIRE) has completed 35 emergency fuels-management projects across 90,000 forest acres. The 2019 Budget Act included $240 million to increase the scale of CalFIRE’s prevention and protection activities including new equipment, more personnel, and planning for forest health. The 2020 Budget Act includes an additional $90 million to further build on CalFIRE’s surge capacity by increasing its air fleet and staffing additional engines in the late fall, winter, and early spring.

On August 13, Governor Gavin Newsom announced a new shared stewardship agreement with the U.S. Forest Service to build on the state’s actions to reduce wildfire risks, restore watersheds, protect habitat and biological diversity, and help the state meet its climate objectives. Chief among these is treating one million acres of forest and wildland annually to reduce risk. The agreement further commits to using science to guide forest management, and to developing a shared 20-year plan for forest health and vegetation treatment that establishes and coordinates priority projects.

California is facing crises on multiple fronts, with COVID-19 being the overriding concern for policymakers through 2020. Wildfires are another California crisis that remains top of mind, as fires rage in both northern and southern California. Through continued preparedness, education, and investment, we can work to lessen our wildfire risk in the face of climate change and other challenges.

Regulators Urged to Accelerate Switch to Net-Zero Economy

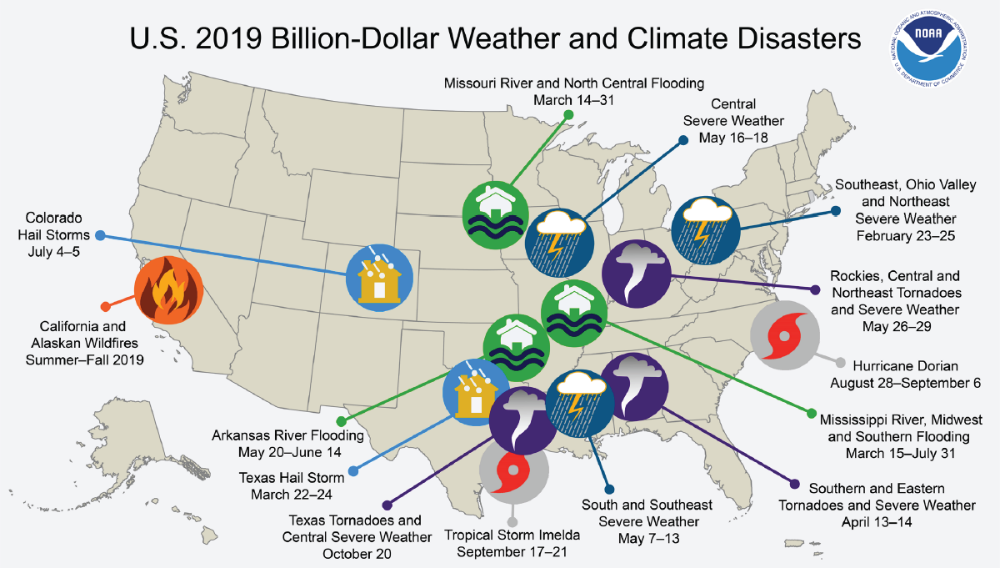

As wildfires raged across the West in late August and two tropical storms threatened the Gulf of Mexico, most people recognized climate change is too expensive to ignore. These challenges are exacerbated by the personal and financial hardships of the global COVID-19 pandemic, which has caused more than 170,000 U.S. deaths and staggering job losses – hitting vulnerable communities hardest, worsening racial and social inequities, and severely straining revenues that support social safety net programs.

To contain the devastation unleashed by climate change and create new jobs of the future, it is imperative to transition to a net-zero carbon emission economy as quickly as possible. In order to limit the average temperature increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius, emissions must be cut in half over the next 10 years and the net-zero target reached by 2050.

The price for missing this target is high. A 2019 National Bureau of Economic Research study found the climate crisis could cost the U.S. up to 10.5 percent of its gross domestic product by 2100. Reaching these goals requires increased investment in low-carbon technology, resilient infrastructure, and energy efficiency. Setting a federal price on carbon will help to kick-start the transition. To have maximum impact, investors need far greater disclosure from corporations and banks on sustainability goals and plans to reach their targets.

The price for missing this target is high. A 2019 National Bureau of Economic Research study found the climate crisis could cost the U.S. up to 10.5 percent of its gross domestic product by 2100. Reaching these goals requires increased investment in low-carbon technology, resilient infrastructure, and energy efficiency. Setting a federal price on carbon will help to kick-start the transition. To have maximum impact, investors need far greater disclosure from corporations and banks on sustainability goals and plans to reach their targets.

To help speed up U.S. efforts to reach a net-zero emission economy, the global nonprofit Ceres (for which Controller Yee serves as a board member) launched its Accelerator for Sustainable Capital Markets initiative with four goals:

- Help large institutional investors align their portfolios with the Paris Agreement goals of limiting global warming.

- Lobby government agencies to regulate climate as a financial risk.

- Work with investors to identify sustainable investment opportunities.

- Focus on corporate board governance to ensure a sustainable future.

In June, the Accelerator issued its first report, Addressing Climate as a Systemic Risk. Already, 40 investors with combined assets of nearly $1 trillion have joined a bipartisan group of elected officials and corporate CEOs in lobbying the heads of seven federal regulators to implement a broad range of actions to integrate climate change across their mandates. The report builds on Ceres’ work over the past 30 years and offers 51 recommendations that can be implemented by financial regulators under their existing authority.

In June, the Accelerator issued its first report, Addressing Climate as a Systemic Risk. Already, 40 investors with combined assets of nearly $1 trillion have joined a bipartisan group of elected officials and corporate CEOs in lobbying the heads of seven federal regulators to implement a broad range of actions to integrate climate change across their mandates. The report builds on Ceres’ work over the past 30 years and offers 51 recommendations that can be implemented by financial regulators under their existing authority.

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) should analyze climate risk impacts on the securities markets and make clear that consideration of material environmental, social, and governance risk factors is consistent with fiduciary duty. The report also recommends the SEC issue rules mandating corporate climate risk disclosure, based on the framework established by the Financial Stability Board’s Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD).

At the direction of the SEC, the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) should assess whether firm audits adequately detect climate risks and issue guidance to help auditors better understand how climate risk affects audits and accounting. The PCAOB also should encourage the Financial Accounting Standards Board to drive consistency in the way climate risk is disclosed in financial statements, and issue guidance encouraging credit rating agencies to provide more disclosure on how climate risk factors are incorporated in rating decisions.

The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) should coordinate with each other and all banking regulators to ensure climate change is integrated into the financial supervision process, to highlight the impact of climate risks on financial performance. In addition, the FDIC should monitor climate risk on bank lending and investment activities and consider how to integrate climate risk into the risk-based premium system.

The Futures Trading Commission should engage other financial regulators on climate change based on findings in the Climate-Related Market Risk Subcommittee’s report, and enhance oversight of climate risk in the commodities and derivatives market.

The Federal Housing Finance Authority should ensure government-sponsored mortgage entities Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae acknowledge the impacts of climate risk on the housing market and launch a formal effort to develop strategies to address climate risk with a particular awareness of the impacts on vulnerable communities disproportionately threatened by climate change.

The Financial Stability Oversight Council has a mandate to identify risks to financial stability. The Council should identify climate risk as a vulnerability and make recommendations on regulations that relevant agencies could adopt. The Council also could coordinate regulatory actions on climate change and the integration of efforts by all financial regulators addressing climate risk to allow for overall financial stability.

Finally, the Ceres report suggests state and federal insurance regulators should acknowledge the material risks climate change poses to the insurance sector and pledge coordinated action to address them. These regulators also should require insurance companies to conduct climate risk stress tests and scenario analyses to evaluate potential financial exposure to climate change risks and require insurers to integrate climate change into their enterprise risk management and U.S. Own Risk and Solvency Assessment processes. In addition, state regulators should require insurance companies to assess and manage their climate risk exposure through their investments and mandate insurer climate risk disclosure using the TCFD recommendations.